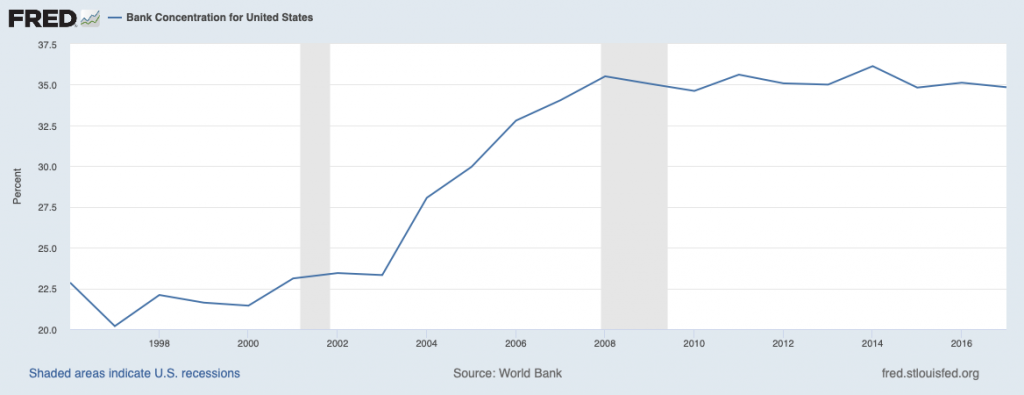

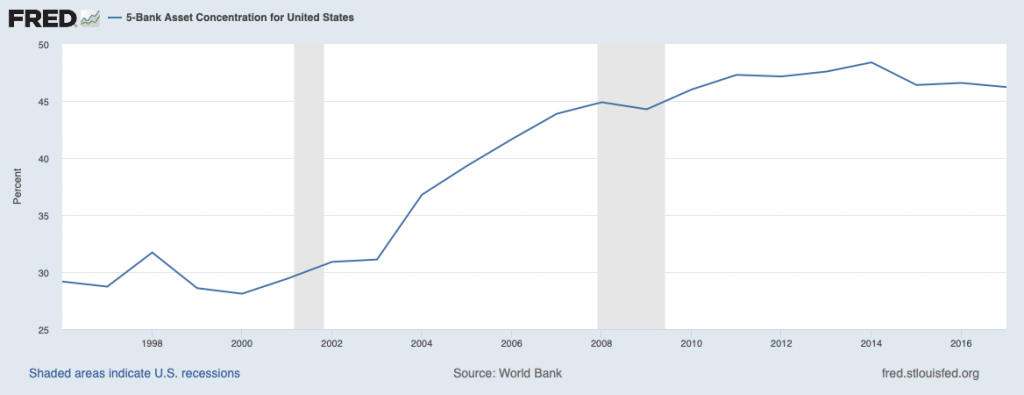

In Tuesday’s Financial Times, Robert Armstrong noted that the discussion on too big to fail in the US needed a new framework for discussion. He states that the impact of economies of scale in the US banking industry have led to higher concentrations. He is rather sanguine on the consequences of this development and notes that it is likely to continue. The concentration in the US can be seen in the following charts (alas data only available through yearend 2017):

A fundamental question to address is the impact of higher concentration. A standard concern is the increased vulnerability of the banking system as it becomes more concentrated – the too big to fail argument. However, it is possible that larger banks lose their capability to meet the needs of local clients – individuals and enterprises – as decision making becomes more centralised and removed from communities. Local community-based banks have historically provided finance for the new entrepreneur whose needs and situation benefit from local knowledge.

This concentration accelerated substantially after 2002. I believe it was driven by two factors: investment requirements for technology and additional regulatory complexity. Both factors create substantial fixed costs that are more easily absorbed by larger banks. Addressing these underlying causes of reduced diversity is essential to preserving a robust banking system that can meet the needs of local communities.